Last Friday I had the honour and privilege of presenting some of the work that our lab does at the 2SLGBTQIA+ in STEM conference in Windsor. The conference was a celebration of science conducted by folks from the Queer communities. It was inspiring and nerdy and so full of Queer joy that it was at times overwhelming – but in an incredibly positive way.

I’ll write another post to summarize some of my thoughts and takeaways from the conference shortly, but I wanted to use this post to share my presentation: Building Bridges With Community-Engaged Computer Science. The text that follows isn’t exactly what I presented – as I have a tendency to go “off script”. However, it includes the major points that I wanted to cover. You can also find the slide deck at the end of this post.

Note: this is a longer-than-usual post.

Slide 1:

Good morning, everyone.

First and foremost, I’d like to thank the conference organizers for inviting me to speak to you today. And thank you to all of you who have come here as members of the Queer communities or as allies. STEM needs you, and your visibility is so important to the people out there who might not be ready to share their truth with the world. Seeing you all here makes me so bloody happy and hopeful for the future.

As mentioned, my name is Dan Gillis. I’m an Associate Professor & Statistician in the School of Computer Science at the University of Guelph. I am a cis-gay man with privilege, and I’m here today to talk to you about my experiences in STEM, and specifically my journey into community-engaged and community-led teaching and research.

My goal is to hopefully convince you why community-engaged work is important, and more than that, how it can build bridges between computer science and STEM, the broader community, and to folks from equity-deserving communities.

Slide 2:

In 2012, I stumbled into the world of community-engaged teaching and research. I say stumbled because I’d like to be able to tell you that I had full intentions of converting my classroom to a community-engaged experience, but that’s not really how it happened – but more on that in a bit.

What I can say is that I have been incredibly fortunate to work with and learn from local leaders and community members who are fighting for social justice. The experiences I have had have opened my eyes to the challenges that our communities face, and how we as academics can learn from, honour, and support the lived experience and expertise of those on the front lines of social justice issues.

To get things rolling, I’m going to tell you a short story about how I actually found myself in the world of community-engaged teaching and research. Following that, we’ll talk about why community-engaged work is important, and how it can foster transferable skills development. We’ll chat about the benefits and challenges with this sort of work – and dive in a bit here on how this can build bridges. I’ll end our chat by describing some of the best practices that I’ve learned over the years, what community-engaged scholarship looks like in the classroom (with a few specific examples), and leave you with some of the outcomes of this work.

So let’s get started.

Slide 3:

As I stated, I stumbled into community-engaged teaching and research. And for me, that really began with Twitter!

Specifically, Twitter allowed me to connect with folks in the community whom I would likely otherwise never have connected with. Over a period of months and years, we talked online about things that were happening in town, and certain challenges that our community faced – such as food insecurity and poverty.

Much of this was mostly complaining about the issues, without necessarily providing solutions or doing anything to address the issues we were identifying.

And then, for whatever reason, things started to evolve. A group decided to get together to meet face-to-face. And that’s when I formally met my co-conspirator, Danny Williamson. After several beers and many chats, we decided that we needed to find a local project that we could sink our teeth into – so that we would move from simply complaining about something, to actually addressing it.

We took numerous meetings around town, in search of a project that would allow us to show that if the two of us twits could make a difference, then anyone could. Our hope was that we could help make even the tiniest of change to address a real issue in our community, but more than that, we hoped that we could demonstrate that if we could do this, anyone could.

But this wasn’t intended to be an academic project. This was supposed to be something Danny and I could do outside of work.

Little did we know what we were about to get ourselves into.

Slide 4:

After numerous meetings, both of us were feeling defeated. None of the meetings provided us with any tangible thing that we thought we could sink our teeth into.

And then we were introduced to Linda Hawkins, Director of the Community-Engaged Scholarship Institute at the University of Guelph in early 2012. During our first meeting, she told me and Danny about the challenges faced by families in Guelph due to food insecurity. Appalled by the statistics, we both felt the need to get involved. And as we learned more and more about the challenges, it became clear to both of us that this was a challenge that students in the School of Computer Science could potentially explore. Serendipitously, a few weeks prior to meeting Linda, I was told that I was going to be taking over a 3rd-year software design course called CIS3750 – Systems Analysis and Design in Applications. To put it simply, the course tasks students with developing a piece of software given a set of formal requirements – typically provided by the professor, and often associated with a video game.

Given that my training was in Math and Stats, I really had no idea how I was going to teach the course because the coding I was familiar with was for mathematical or statistical analyses – not software design. Further, I am not a gamer – unless we’re talking Super Mario Brothers or old-school Nintendo or Super Nintendo games.

I was nervous about taking on the course. I was also nervous about redesigning the course to introduce the students to a real-world challenge that was well outside of my scope of expertise. When I chatted with my Director at the time, he suggested it was a bad idea to bring community into the classroom – suggesting that it was destined to fail and that it would be a lot of work.

For whatever reason, my gut told me to carry on – so I set about redesigning CIS3750.

In the fall of 2012, I introduced a semester-long project called Farm To Fork to the students in CIS3750. The goal was to have students develop a tool that would improve the communication between the emergency food responders in the community with those who had the means to donate. That is, we wanted folks who could donate to the local food bank and pantries know that dried beans, pasta, and peanut butter – while great – did not really meet the needs of those who were food insecure. In short, we wanted to provide donors with an up-to-date list of items that were needed by folks in our community.

I was nervous about introducing the project, unsure of how the students would respond to this type of a challenge when most were expecting to build a video game. Fortunately, my fears were quickly silenced as the students demonstrated their ability to not only take on the challenge but to go above and beyond to develop a system that sparked interest around the globe.

The results were beyond anything I could have imagined. And engagement was through the roof. Throughout the semester, class attendance was 95% or higher.

Of the 30 students in that first class, roughly 2/3rds continued to work on the project outside of the class – officially launching the app to the community in the fall of 2013.

Slide 5:

At around the same time, I got to know a bunch of the students. In fact, I made it a point to show up to as many of the student-organized events that I could so that I could get a better sense of who they were. While I was very familiar with math/stats students, computer science students were new to me.

This allowed me to connect to various community events that brought together tech-nerds to chat about tech and basically geek out. It was eye-opening and awesome. And it introduced me to the idea of a hackathon – where computer nerds get together to create apps or programs that do something.

After the success of the Farm-To-Fork class, I realized that hackathons would be so much better if they included more lived experience and expertise. I thought, if I build a hackathon, it can’t just be computer science students. It needs other nerds from other disciplines, and importantly, it needs community nerds.

Thus was born a series of hackathons at the University of Guelph that brought together interdisciplinary teams of students to address broad social challenges – such as mental health, sustainability, food waste, etc.

Slide 6:

The hackathons were a huge success – and connected so many students with community experts, and folks outside of their domain.

However, the problem was that these events weren’t as accessible as I would have wanted. While extracurricular activities and events are amazing – there are groups of students who can’t participate fully for a variety of reasons – jobs, caregiving, etc.

With this in mind, and with the help of my brilliant co-creator, Dr. Shoshanah Jacobs, the Ideas Congress classroom was born. The goal was to create a semester-long hackathon that brought together teams of students from as many disciplines as we possibly could, then connect them with a real-world social justice challenge provided by a community partner. Students would not only have to learn to work together, but they would also have to learn how to communicate with our community partner to truly understand the challenges they faced.

Thinking back to Farm To Fork – students initially saw the challenge as that of solving food insecurity. In reality, and by the end of the semester, students realized that the project wasn’t going to solve food insecurity, but it would bridge the communication gap that provided support to those who were food insecure.

ICON acted the very same way – but instead of just computer science students, the class included disciplines spanning upwards of 26 majors, 6 colleges, all year levels of students, a community partner, and interdisciplinary faculty expertise.

Clearly, community-engaged scholarship was becoming a standard in my day-to-day life.

Slide 7:

Eventually, community-engaged scholarship was joined with community-engaged research. And to this day, my four major research programs – which may seem disparate and mutually exclusive – all fall under the umbrella of community-engaged and community-led work.

As a stats nerd, my initial research was focused on the area of ecological and public health risk assessment – specifically developing and applying new statistical methods to understand factors that affect ecological or public health.

After the Farm To Fork class, I suddenly found myself exploring the world of community-engaged software design. With the development of the various interdisciplinary hackathons and the Ideas Congress classroom, I added transdisciplinary pedagogy and the scholarship of teaching and learning to my list of research programs. Finally, after being invited into an Inuit community in Nunatsiavut, I expanded my programs to include bridging the digital divide – which brings together the power of mobile ad hoc networks and computer science, with Inuit expertise.

Now, when I chat about the work that I get to do with students in the various courses I teach, or the lab we share – I often hear “Wait, didn’t you say you taught computer science?” or “it’s amazing that the students are doing something to help their community, but I never would have thought computer science students would care about something like this.”

I think this sentiment needs to change. I think the world needs to know that computer science (and STEM) students are more than just coders or tech nerds, they are more than cogs in a machine that works to increase website clicks, or redirects folks to more products they should buy. I want computer science students to enter the domain knowing that they are going to solve real challenging problems – but that they also need to do this with a variety of other types of expertise.

Slide 8:

Of course, beyond the fact that students should be tasked with real-world challenges, and beyond the fact that students should be able to work across disciplines (not to become domain experts, but to work with other types of expertise), I have seen how community-engaged work can foster what’s known as “transferable skills” – also called soft or foundational skills.

Slide 9:

About 6 years ago, I saw this particular post on Twitter.

How do we all feel about this?

When I read this, my skin crawled. But I also recognized this attitude. I used to have it – because I was trained in STEM and somehow the arts or social sciences were always seen as “lesser”. Fortunately for me, I was exposed to non-STEM researchers when I began my PhD – working with folks from the Public Health Agency of Canada on Scenario Analysis. Watching qualitative and non-STEM researchers do what they do was eye-opening and mind-blowing. The things they can do are incredibly valuable, insightful, and without a doubt – absolutely necessary.

Anyway, whatever my experience was, the sad reality is that this attitude is pervasive. Not just with students – but with faculty as well.

Slide 10:

And it speaks to the problem of siloing our degree programs. That’s not to say that learning about a specific discipline is bad – it’s not. We do it rather well, and it has done a lot to benefit society. But given our big challenges, we need to start bridging the gaps between our disciplines.

Because no single discipline is going to solve the big challenges we currently face. Math won’t solve climate change on its own. Chemistry won’t solve hunger on its own. Sociology won’t fix poverty on its own. We need to learn to work together.

Otherwise, we are only going to see the world through the lens of our discipline – reducing every problem to a nail that “fits” with the hammers we’ve been trained to use.

Slide 11:

Of course, I’m not the only one nor the first to call into question the siloed training universities typically embrace.

A 2018 report from RBC – called Humans Wanted – described the major skills that industry had identified they wanted/expected recent graduates to have. The top 18 were not technical skills. In fact, the skills identified as necessary to thrive in our future skills economy were the so-called transferable skills.

Slide 12:

Dr. David Nabarro – special advisor to the UN Secretary-General on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and Climate Change, and Special Envoy for the WHO on COVID 19 – visited Guelph in 2019. At that time, he insisted that:

“We are destroying our ability to solve our biggest challenges by insisting on very focused and ever-more-siloed disciplinary thinking and training.”

In other words, students need to be given the space to learn about, identify, and practice the transferable skills that will allow us to address broad social challenges that are not the domain of a single discipline.

Slide 13:

But what are these skills that students need?

And what do they have to do with community-engaged scholarship and research?

These skills include such things as active listening, teamwork, communication, and openness to other ways of knowing the world.

And, in fact, these skills are necessary when working with community partners – especially if those community partners do not speak the same STEM languages that we speak. We can’t help solve a problem in our community if we don’t listen to the people at the front lines of whatever social justice issue they are addressing. We can’t honour their expertise and lived experience if we assume we know what’s going on, if we assume we know what the solution is before we even have a minor understanding of the challenges they face.

Interestingly, I think that folks in this room, and folks from other equity-deserving communities are perhaps uniquely situated to have, based on systemic inequities and societal prejudices, experience and practice with these skills. We learn to adapt, actively listen, and communicate in ways that help us remain safe and protected. And by the sheer force of discrimination, we have had to and continue to work as a team to fight back – despite our differences, despite our lived experiences – and we’ve had to learn how to communicate to ensure that our voices are heard so that those who come after us will have a better world.

Slide 14:

Okay – so let’s pause for a second.

We’ve heard the story of how I stumbled into community-engaged scholarship and research.

And we’ve heard how community-engaged work can foster transferable skills development with students – skills that are necessary to thrive in our future skills economy and to solve our big challenges.

And you might be thinking – yeah – this makes sense – and also, why the hell aren’t we doing this ALL THE FREAKING TIME?

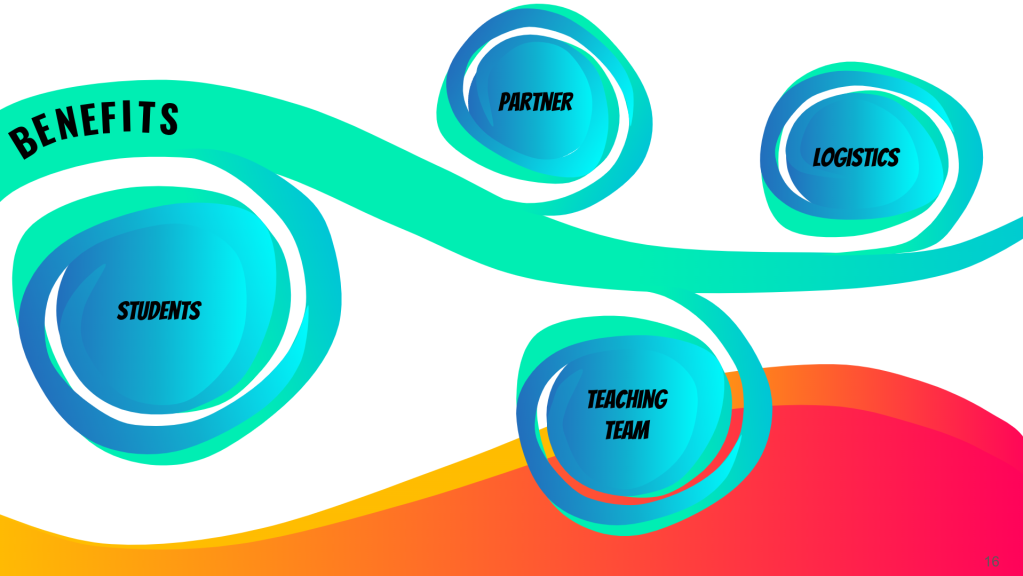

Slide 15:

The answer to that is simple. Community-engaged work comes with a set of both benefits and challenges.

Let’s start with the challenges – and please note that this is not an exhaustive list.

Students:

- in the past, I have had students complain that working on not-for-profit challenges is akin to me forcing them to provide free labour and that they shouldn’t have to be burdened with my “save the world shenanigans”. This doesn’t always happen, but there is a chance that there will be push-back from some students – which means a plan needs to be in place to address this.

- Students often feel that they must become domain experts (both in Computer Science/Software Engineering and whatever problem the community partner faces). This is not the case – however, it is important for the students to learn as much as they can from the domain experts (i.e. the community partner) so that they can understand the problem and develop an appropriate solution.

- While working with not-for-profits and charitable organizations often quells any issues related to intellectual property rights (since students recognize that money-making is not the goal of the solutions they develop), there is still a need to be clear about their rights, and to provide alternatives to those who aren’t comfortable sharing their work.

Partner:

- The partner may expect that their project will be completely finished by the end of the semester. This is unlikely to happen. Instead, what usually comes from the class is a well-defined prototype that can be worked on beyond the classroom in a number of ways. This may involve students completing the work using independent study courses, or perhaps getting paid internships, or through volunteer time, or it could involve passing the work on to the organization itself.

- Further, the community partner needs to be aware that the end product may not be what they were expecting. Sometimes this happens because the path the students take is unexpected. More often, however, this happens because I have had to make decisions to support the learning outcomes of the course.

Teaching Team:

- From a teaching perspective, as class sizes continue to increase, it becomes more and more challenging to provide immediate feedback to students.

- After spending months organizing things with the community partner prior to the students joining the class, there is still the potential that the students won’t engage like you expect them to. This can be demoralizing to the teaching team.

Logistics:

- From a logistics perspective, it is important to consider who the classroom partner will be. It’s also important to consider what might happen if some or all of the students are unhappy with the project that was selected. What if they were fundamentally against the social justice issue that was presented by the community partner? For example, what might happen if this sort of class were being offered in Texas or Florida right now, and the social justice issue that was selected was that of queer/trans rights or reproductive rights?

- Another challenge associated with the course is the sustainability of the solution, ownership of the project, data sovereignty, etc. These are important things to consider and discuss with the partner and the class so that everyone is on the same page, responsibilities are set, and surprises are kept to a minimum.

Slide 16:

Clearly, I don’t want to present just the negatives/challenges, so before we carry on, I want to chat about the potential benefits of community-engaged work (beyond what we’ve already chatted about).

Students:

- The connection with community means that students get to see what’s happening in their community and the challenges faced. From my observations over the years, this seems to have increased their civic-mindedness, or at least shown them that there are other things they can do with a computer science degree that engages and supports the community beyond increasing clicks to a website or selling products.

- I have seen a substantial difference in how students engage with this sort of work – both in the class and outside – compared to non-community-engaged courses. Feedback indicates that the students feel more connected with their work because the work isn’t a disposable one-off that meets the demands of the professor – but instead is something that could meaningfully make changes within the community.

- I can’t say enough about how community-engaged work seems to foster the development of transferable skills. This will support students in the future skills economy, or if they opt to continue to do research.

Partner:

- For the partner, there is a benefit to having so many brains working on a challenge that they likely don’t have the time or resources to address (because they are devoting all of their resources and time fighting whatever social justice issue they are addressing).

- There is also the potential benefit of increasing brand recognition. That is, not-for-profits and charitable organizations have the opportunity to increase their audience by connecting with students, their parents/caregivers, etc.

Teaching Team:

- For me, one of the biggest benefits is the level of engagement that I typically see in the classroom. Students aren’t just sitting there absorbing information to regurgitate on an exam. They are brainstorming, collaborating, and challenging preconceived notions and ideas. It’s brilliant, and it makes me smile every damn time I see it.

- And of course, it is absolutely amazing to get to witness the inventive solutions they develop. It’s so fulfilling, heartwarming, pride-inducing, and all sorts of awesome.

Logistics:

- The work that the students do is done as a collective. That is, the entire class is working on one project – as a giant team – building up each other instead of competing. Yes, they also work in smaller teams to make things easier to manage and grade, but the stages where students are trying to understand the problem are completed together – great ideas are shared, lesser ideas are critiqued and possibly discarded, definitions are formalized, and knowledge gaps or misunderstandings are identified.

Slide 17:

So yes, we have benefits and challenges with community-engaged work, particularly in the classroom.

But what does it actually look like in a classroom? How best can we implement it? What I’m about to present to you are some of the “best practices” that I have identified after more than a decade of this sort of work.

Slide 18:

For everyone involved – students, partners, the teaching team – it is absolutely necessary and important to set expectations. Set them early. Repeat them often. Then repeat them again. This is to help avoid any disappointment that students might feel if/when they don’t complete the project in a single semester. It’s also to ensure the community partner knows that the learning outcomes take priority, that the project likely won’t be finished by the end of the semester, and that there is a chance that students won’t want to finish the project through independent study courses.

It’s also important, as previously mentioned, to discuss intellectual property rights. In this case, I would suggest that the students set up an open-source solution and that the partner is limited to a not-for-profit or charitable organization.

I think it is also important to remind everyone to trust the process. This sort of work can feel unorganized and disjointed at times. Everyone needs to remain open to arising challenges and how they might affect timelines and deliverables. In particular, community partners may need to cancel a class meeting at the last minute because they need to deal with a wide assortment of challenges that they face daily. It’s important that the teaching team remain calm while supporting any anxieties that might arise within the students. Often focusing grades on the process instead of the final deliverable helps.

For those students who aren’t comfortable working on the project, it’s important to have an alternative project set up. If I recall correctly, I’ve only had to rely on this once with a single student since I started bringing community partners into the classroom.

Finally, it’s important that work with the community partner begins early – which brings us to the general timeline of the course.

Slide 19:

When the students arrive in the class for the first time, they aren’t necessarily interested in all the work that goes into bringing a community-engaged classroom to life (although, I think it is important to share this info with them). Their focus is typically on the 12 weeks of the course, and what we’re going to be doing. The first 4 weeks are typically devoted to problem identification and planning (where students work with the community partner to truly understand what the challenge is). The next 4 weeks are devoted to finalizing planning and beginning a variety of different prototypes that are shared with the partner. The last 4 weeks are for finalizing the prototypes and wrapping things up.

What the students don’t see, however, includes months of work. Prior to the course – I typically spend my time collecting a list of potential partners, mapping their challenge to the course learning objectives, picking one of these partners based on the best fit to the learning outcomes, setting up the course outline, setting priorities and expectations with the partner, and finally welcoming students to the classroom. Following the course, there are a number of things that could happen, but this often involves working with the partner to share what the students have done or bringing on students to complete the work. Depending on the situation, it might also involve fundraising to support ongoing development.

So now we know why community-engaged work is important, and how it fosters transferable skills. We also now know some of the challenges and benefits of bringing it into a classroom, and what the timeline of each iteration of a community-engaged course looks like…

But what does it look like on the ground, in the classroom? What are the students doing? And how are we providing space for them to practice their transferable skills?

Instead of assuming that they will pick up transferable skills on their own, a community-engaged course should include numerous activities to allow students to think about their understanding of the world. We’re going to dive into a few examples now…

Slide 20:

Communication with the community partner is clearly very important. To facilitate this, and prior to meeting the community partner, students learn about the importance of communication – how to ask questions and how to talk to people who might not be “computer science” people.

One of the first things we cover is something called the “Good Questions Lab”. It begins by asking the students to identify a colour.

Typically the answers range from (for this example) blue to blue-green to aqua. Sometimes it includes HEX codes or RGB codes. Sometimes answers include short stories about what the colour reminds them of. And some other students will indicate they don’t know because they are colourblind.

We then move on to the next question…

Slide 21:

In this case, we ask “how blue is this colour?” and provide the students 5 different possible answers.

Slide 22:

Lastly, we ask “Is this colour blue?” – with a binary response of yes or no.

When this is finished, we discuss the types of data that each of these questions provided and discuss the differences between open-ended and closed questions.

Students are then asked which type of question would work best when we are first chatting with our community partner. Almost always (at least in my experience), STEM students seem to assume the latter 2 versions of the questions – closed questions – are the starting point.

These types of questions, however, do not allow our partners to share their story in a way that is meaningful to them. And while we might not know at that moment if or how what they share with us will be useful for design, we have to recognize that the information they opted to share was important to them, and we should give them space to tell that story. They are the experts in this domain, so we can’t throw away anything they tell us as unimportant. And based on my experience, there are always nuggets of information that seem unimportant or unrelated to the problem at hand – but these always end up being important for the design of the solution.

While open answers take more time to document, and more time to evaluate, they provide the knowledge that will allow the students to truly design a solution that meets the needs of the community partner.

Slide 23:

We also explore language and the challenge of using tech-speak on community members who might not be tech people. Or the fact that they will likely use language that we won’t understand. The words on their own will be understandable, likely, but the context and their meaning together might be beyond our expertise and understanding.

To explore this, students are presented several english language statements and then asked to explain what they mean. They are often fun or ridiculous statements, but they very quickly get the point across that language can cause misunderstandings and confusion if we don’t take the time to be humble and ask what someone means by what they are saying.

This first example is a convoluted way of saying that folks were asked to answer true or false questions. I have no idea why it had to be stated the way it is. The language used provides no nuance and acts as a barrier to understanding more than anything.

Slide 24:

The next example is a proper English sentence that essentially means that

“Bison from Buffalo, New York, who are intimidated by other bison in their community in turn intimidate other bison in their community.” This is another example where language acts as a barrier to understanding.

Slide 25:

Before I end, I just wanted to briefly talk about some of the outcomes that community-engaged teaching and learning have created…

Slide 26:

First and foremost, students have had access to the expertise of so many community partners. Folks who are experts in food insecurity, food waste, knowledge mobilization, health and wellness, mental health, public health, and more…

Slide 27:

More than 2000 students (to date) have gone through these various community-engaged courses, and they have worked with more than 55 community partners.

The number of hours that these students have contributed to the community range somewhere between 318k and 382k. And assuming an average co-op wage of $25 per hour, this represents $8.0 to $9.5 MILLION contributed to the local community.

But what do students think about this sort of class?

“The CES approach empowered us to create better solutions, enhanced our learning experience, and provided a sense of ownership over what we created. It is safe to say that the projects were the only projects in our collective university careers that are still used to this day to help the community.” ~ former CIS3750 student.

What about the co-op officers who work with both students and employers every day?

“Students who are trained this way have a unique mindset. They think about problems differently from most computer scientists. It is not just about solving a problem efficiently. It also becomes about how to take into account different perspectives, whether it is the client, other disciplines or other collaborators in a project. This is a critical mindset to have in modern computer science in order to solve real-world problems and to be good citizens. There must be a strong theoretical basis, but without this interdisciplinary, community-driven mindset it is impossible to avoid the mistakes that companies like Google, Facebook and others have made where the rights and privacy of users are sacrificed for profits.” ~ co-op officer.

“These students are differentiated from others. We hear consistently from employers that these students are excellent communicators with a particular focus on social justice, civic-mindedness and giving back to others. The high level of collaboration required from students working with community partners provides students with excellent communication and team-building skills with which to apply in future co-op work terms and beyond.” ~ co-op officer.

Community-engaged teaching and learning was not what I ever expected to be doing when I started my PhD in Statistics so many years ago. But I have seen the power it has to change the lives of students, to affect change in our community, and to create spaces where all students can thrive – regardless of who they are, how they identify, or where they come from.

I’m not going to say it’s the be-all and end-all. It’s hard work. It’s time-consuming and challenging. But holy hell, it is so bloody worth it. And I hope I have convinced you that it’s worth it too.

Thank you

1 Comment